Name the first thing that comes to mind when you think about Jackson Hole. Skiing? Grand Teton National Park? The Wild West? I’ll wager you didn’t immediately settle on the image of an elite scientific research lab that is hot on the heels of cures for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS. However, just such a lab exists right in the heart of downtown Jackson. And, as it turns out, this rural corner of western Wyoming is the perfect setting for the revolutionary work happening in the Brain Chemistry Labs at the Institute for EthnoMedicine. That’s right: thanks to the pioneering work happening at a not-for-profit lab in a cabin in Jackson, Wyoming, the world may very soon have highly effective treatments for some of the most devastating and widely-suffered diseases on the planet.

If you happen to be a regular reader of the two-century-plus-year-old biological research journal Proceedings of the Royal Society, you’ll already know about the Institute team’s efforts – after all, their paper, “Dietary exposure to an environmental toxin triggers neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid deposits in the brain,” which was only published in January of this year, is the second of the top three most-read articles in the history of the venerated journal. However, since I’m guessing that you, like me, don’t often thumb through the latest copy of Proceedings, I’ll elucidate.

It’s helpful to start with a definition of ethnomedicine, since this field is the at foundation of the Institute team’s work. As senior scientist and ethnobotanist Sandra Banack and molecular biology research associate James Powell explained to me in a recent interview, ethnomedicine is the study of patterns of wellness and disease among indigenous peoples, and the study of botanical cures for illnesses. If you think this area of specialization might sound a little archaic, remember that, as Banack and Powell point out, twenty-five percent of modern pharmaceuticals come from plant-based medicine. In other words, ethnomedicine is a crucially relevant topic.

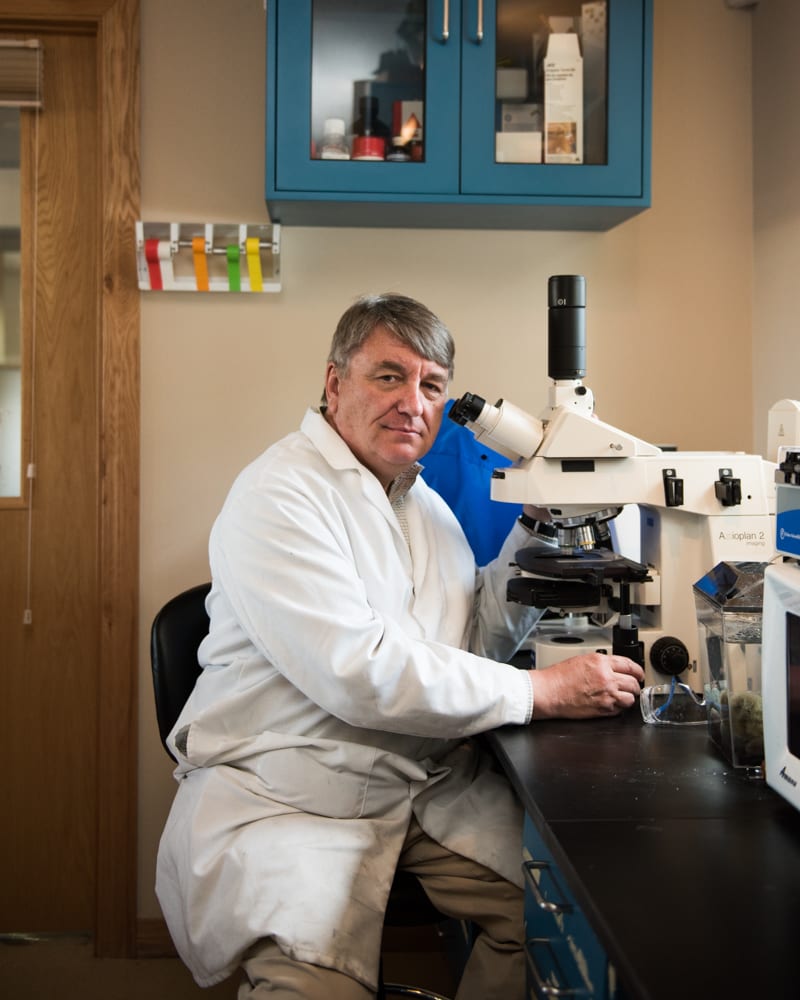

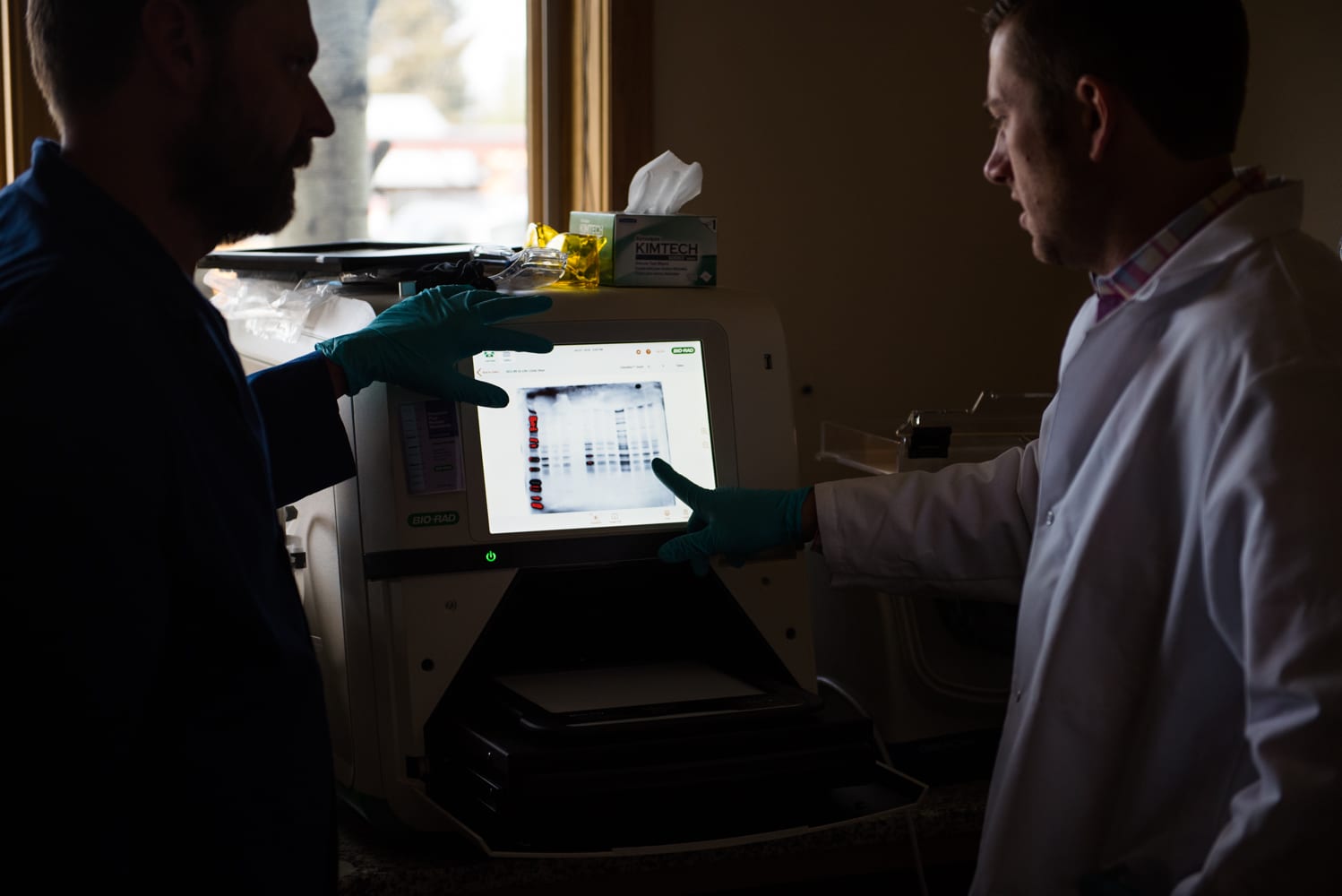

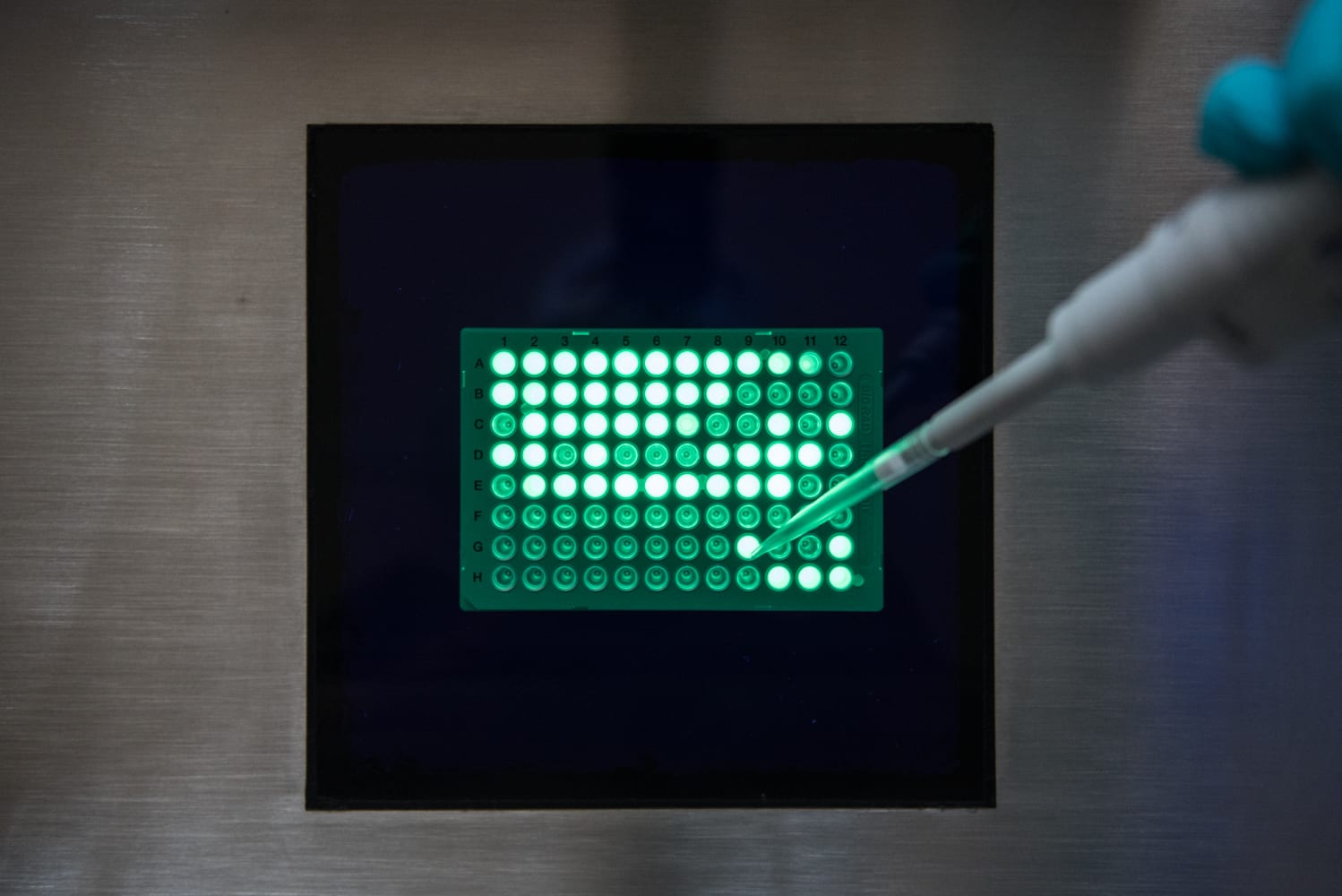

Indeed, for many years, the Institute’s executive director Paul Alan Cox, an ethnobotanist like Banack, has studied neurodegenerative disease in indigenous cultures around the world, both attempting to discover causes and possible botanically-based treatments. A turning point occurred in the late 1990’s when, before the Institute was founded, Cox began investigating the high rates of dementia suffered by Chamorro villagers in Guam. With the help of his early associates and further research among other cultures with higher-than-average rates of neurodegenerative disease, Cox eventually hit upon the monumental discovery that there is an environmental factor – the neurotoxin BMAA, which is produced by cyanobacteria found in blue-green algae – directly related to the development of neurodegenerative illness. Fast-forward through the Institute’s official inception in 2005 to today, and its team has produced two separate pharmaceuticals, both currently undergoing FDA approval, that help stem the deleterious effects of BMAA in the brain, and it has a third drug currently in development. That’s right: thanks to the pioneering work happening at a not-for-profit lab in a cabin in Jackson, Wyoming, the world may very soon have highly effective treatments for some of the most devastating and widely-suffered diseases on the planet.

You might rightly expect this kind of world-changing research would be happening at big universities or top-secret corporate labs. However, it turns out that Jackson Hole is actually the ideal place for the Institute. For one thing, the lab’s nonprofit status, which Banack points out is an unusual model in the world of scientific investigation, fits perfectly in a highly philanthropic, community-oriented place like Jackson. While the Institute is supported by the occasional government funding, the majority of its capital comes from engaged citizens of nearly all income levels who want to see a cure within their lifetimes for neurodegenerative illness. Banack explains that without the many hoops involved in running a for-profit business – no bureaucracy, no shareholders to answer to – the lab’s scientists are able to do their jobs at maximum efficiency and thus come much closer, much faster, to helping do away with the specter of neurodegenerative disease. As Banack notes, “The only people we work for are patients and their families.”

The Institute’s unconventional business model also allows its core members (Cox, Banack, and Powell, as well as senior researcher and cyanotoxin specialist James Metcalf and senior research fellow in cell biology, Rachael Dunlop) to easily cooperate with a consortium of other experts worldwide, all of whom are passionate about finding cures for neurological diseases. And, not surprisingly, the group’s international colleagues love to make business visits to Jackson Hole. Indeed, Banack and Powell emphasize that the lab’s location in a place that offers so much in terms of outdoor recreation and experiences in wild nature actually fosters the team’s best thinking – there’s nothing like a refreshing winter ski or a hike around Jenny Lake to recharge a weary scientist’s brain. Additionally, thanks to the Internet, any resources they need that can’t be found locally are only a few clicks away. “Modern technology has enabled us to do this work from virtually anywhere,” Banack says, “so why not do it in one of the most beautiful and inspiring places on Earth?”

To learn more or to help support the team’s work, you can find the Institute online at www.ethnomedicine.org. The team keeps an open-door policy at the lab and encourages visitors. The recent Proceedings paper mentioned above can be found here. The Institute will also host a screening of Hunt for the Hidden Killer, a film about the scientists’ work, at the Jackson Hole Center for the Arts on Tuesday evening, June 28th,2016.

Images © Taylor Glenn